Introduction

GBS virus (Guillain-Barré Syndrome ) is a rare but serious autoimmune disorder where the body’s

immune system mistakenly attacks the peripheral nervous system. This can lead to muscle

weakness, paralysis, and other serious health complications. Although GBS itself is not a virus,

it is often triggered by infections, including certain viral infections. Understanding the

relationship between GBS and viral infections is crucial for effective diagnosis, treatment, and

prevention.

Historical Context and Discovery

GBS virus was first described by French neurologists Georges Guillain, Jean Alexandre Barré, and

André Strohl in 1916. They identified the syndrome in two soldiers during World War I,

highlighting its acute onset of muscle weakness and abnormal reflexes. Since then, GBS has

been extensively studied, revealing its complex relationship with the immune system and

infectious agents.

Etiology and Pathophysiology GBS VIRUS

GBS virus is an autoimmune disorder, meaning the body’s immune system attacks its own nerves.

This attack primarily targets the myelin sheath—the protective covering of nerves—leading to

demyelination and impaired nerve signal transmission. In severe cases, the axons themselves

may be damaged.

The exact cause of GBS is unknown, but it is often preceded by an infection. Common triggers

include:

1. Campylobacter jejuni: A bacterium often associated with food poisoning.

2. Cytomegalovirus (CMV): A common virus that can cause severe illness in immunocompromised individuals.

3. Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV): Known for causing infectious mononucleosis.

4. Zika Virus: Notoriously linked with the GBS virus during the 2015-2016 outbreaks in South America.

5. Influenza Virus: Both natural infections and certain flu vaccines have been associated with GBS, though the risk from vaccines is very low.

Clinical Presentation

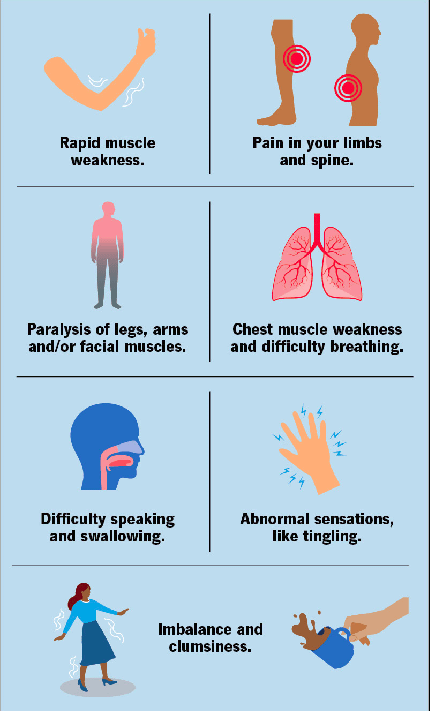

GBS virus typically begins with tingling and weakness in the extremities, which can rapidly progress to more severe muscle weakness and paralysis. The hallmark symptoms include:

Symmetrical Weakness: Starting in the legs and moving upwards.

Areflexia: Loss of reflexes.

Paresthesia: Tingling or “pins and needles” sensations.

Pain: Often reported in the back and limbs.

In severe cases, the GBS virus can affect the respiratory muscles, requiring mechanical ventilation. Autonomic dysfunction, which affects heart rate and blood pressure, is also common and can be life-threatening.

Diagnosis

Diagnosing GBS virus involves a combination of clinical evaluation, patient history, and diagnostic tests. Key diagnostic tools include:

Lumbar Puncture: Elevated protein levels in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) without a corresponding increase in white blood cells (albuminocytologic dissociation) is a typical finding.

Nerve Conduction Studies (NCS) and Electromyography (EMG): These tests measure the speed and strength of nerve signals, revealing characteristic slowing or blockage of signals in affected nerves.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): This may be used to rule out other conditions and can sometimes show nerve root enhancement.

Treatment

There is no cure for GBS, but several treatments can reduce the severity and duration of the illness. The primary treatment approaches include:

Plasmapheresis (Plasma Exchange): This process removes antibodies from the blood, reducing the immune system’s attack on the nerves.

Intravenous Immunoglobulin (IVIG): High doses of immunoglobulins are administered to help block the damaging antibodies.

Supportive care is crucial, particularly for those with severe weakness or respiratory involvement. This may include physical therapy, occupational therapy, and measures to prevent complications such as deep vein thrombosis and pressure sores.

Prognosis and Recovery

The prognosis for GBS varies widely. Most individuals experience a significant degree of recovery, although it can take months to years. About 60-80% of people are able to walk independently at six months. However, some may experience residual weakness or other long-term effects.

Factors influencing recovery include:

Age: Younger individuals tend to recover better.

Severity: More severe initial symptoms often predict a longer recovery time.

Timeliness of Treatment: Early intervention with IVIG or plasmapheresis can improve outcomes.

Research and Advances

Research on GBS virus is ongoing, with recent studies focusing on:

Genetic Susceptibility: Understanding why certain individuals are more susceptible to GBS following infections.

Improved Therapies: Developing more effective treatments with fewer side effects.

Vaccine-Associated GBS: Ensuring the safety of vaccines and identifying those at higher risk.

The role of infections, particularly viral infections, continues to be a significant area of research.

For instance, the Zika virus outbreak provided insights into how viral triggers can precipitate GBS, prompting further investigation into viral mechanisms and immune responses.

Public Health Implications

Understanding the GBS virus and its triggers is essential for public health. Efforts to monitor and control infections that can precipitate GBS, such as through vaccination and sanitation, are critical. Additionally, awareness and early recognition of GBS symptoms can lead to timely treatment, improving outcomes for affected individuals.

Conclusion

Guillain-Barré Syndrome is a complex and potentially severe condition with a strong link to infectious agents, particularly viruses. While significant progress has been made in understanding and treating GBS, ongoing research is essential to unravel the intricacies of its pathogenesis and improve patient care. Awareness and early intervention remain key to managing this challenging syndrome effectively.